Day Dreaming of a Living Wage Grand Compromise

The debate over the minimum wage has been very frustrating. Tedious arguments and dueling strawmen abound. Let me summarize some obvious points about the discussion, and then propose a solution that addresses the concerns of both sides.

First: If you raise the minimum wage high enough, jobs will be lost. If the average wage in a city is $30 an hour, and you raise the minimum wage to $60, you would literally make it impossible for most people to be employed. As a mathematical certainty, at least half the labor-force would be unemployed or on the black market.

Second: If we know that a massive number of jobs would be lost with a $60 minimum wage, then for each incremental increase up to $60 some portion of jobs must be lost. As the minimum wage rises to $12 an hour, to $18 and hour, and upward, some portion of the workers fomerly earning $8 simply cannot find work. The job loss won’t necessarily be linear with increases in the minimum wage. But as a matter of logical certainty, it must happen.

Third: If the minimum wage is raised an insignificant amount, then the impact on job loss will be impossible to measure. If only 5% of the population is earning minimum wage, and you raise the minimum wage by 10%, then the impact on jobs will be overwhelmed by statistical noise. This is especially the case because you would expect a very delayed response between a wage hike and unemployment. A firm is not going to instantly fire trained and well-functioning employees. Rather, the firm will be slightly quicker to fire, and slightly slower to hire new workers. There is much debate over various empirical studies, but the debate can never be resolved because it is fundamentally impossible to measure such small effects when there are so many confounding variables.

Fourth: Wages are not purely proportional to utility created. Rather, wages are a function of utility created and bargaining power. Some economists argue that if wages are too low, the answer is to give people skills to make them more productive, to enable them to take advantage of technology. But consider the rubbish man. He does take advantage of technology. Sanitation technology allows a few garbage men to cover a large territory and create a massive amount of utility. But he earns a poor wage because he is a commodity worker, he is replaceable. A sanitation worker’s income is proportional to his ability to unionize, proportional to his bargaining power. And becoming more efficient, having technology replace labor, can mean less bargaining power. For instance, junior lawyers make less money now, because there are far more law school graduates and the discovery work has been automated with computer searches. The fact is, we have a global glut of commodity labor. It is often the non-technological enabled jobs that still make the most money – such as the senior lawyer who has rare and intricate knowledge of corporate law. The modern laborer provides valuable services, they do leverage technology, but they earn low wages due to low bargaining power.

Fifth: It is theoretically possible to have a situation in which significantly raising the minimum wage has little negative impact on jobs. And I’m not talking about the monopsony model taught in econ textbooks. That model obviously does not apply in the real world. Here is my theoretical model:

Imagine the following situation: In a certain island, five landlords own a combined total of 50 acres of land. There is a labor pool of 100 farmers. At full output, each farmer has the potential to farm 1 acre and produce 50 bushels of wheat. Thus we have a substantial excess of farmers. What happens? The wages of farmers will tend toward subsistence. The landlord might only allow the farmer to keep 20% of their output, a mere 10 bushels. If a farmer objects, the landlord will fire him, and replace the farmer with a desperate unemployed person from outside the labor pool.

Now imagine that the farmers band together, form a union, and collectively bargain. They set a minimum wage across all the land of 25 bushels. In this scenario, all the farmers end up being better off. No farmers get fired, because the landlord still wants all the plots of land worked.1

The minimum wage can raise wages if the employers are 1) highly-profitable 2) enjoy high barriers to entry 3) command at least a partial monopoly and 4) cannot easily replace workers with automation or outsourcing. In such a case, their output is not limited by labor. Thus if labor costs rise, they still produce the same output and employ the same number. The increased pay to labor will simply come out of the profits.

Sixth: The above theoretical possibility most likely does not apply to the specific cities that are looking to enact a $15 minimum wage. Many minimum wage jobs are at restaurants. Restaurants are generally not wildly profitable, so to pay their workers they will have to raise prices. If they raise prices, people will eat out less and just make dinner themselves. So some dishwashers at the remaining restaurants will earn more, other dishwashers will be fired as the restaurants close, and will find it very hard to find new work. To the extent that these cities already have nasty unemployment problems – in Philadelphia, for instance, 19% of black residents are currently unemployed – a higher minimum wage could make things much worse.

OK, so what do we make of all these somewhat contradictory points? Well let us step back. What goal are we trying to accomplish with a minimum wage? The goal is to transfer money from all those with a good bargaining position and high income, to workers with a poor bargaining position and low income.

But a minimum wage is a poor vehicle for accomplishing the goal of wealth distribution. Yes, some employers of minimum wage workers are wildly profitable. But many are not. Many are mom and pop stores, scraping to get by. Many big box retailers like Sears and Best Buy are treading water. To the extent that the wage increases get passed on to the customers, again, these customers are often not very wealthy. Meanwhile, wildly profitable companies such as Google, Apple, JP Morgan, and their wildly rich owners, do not bear any of the burden, as they employ few low wage workers.

There is a known way to redistribute money based on who actually has high-income: the graduated income tax. Also, there is a way to ensure that the minimum wage does not create unemployment: set a floor at which jobs are guaranteed.

Thus, here is the sensible way to do a minimum wage:

- Permanently peg the minimum wage to be some percent of the average wage. We could make it 45% – which comes out to $15 an hour.2 As total wages rise with inflation, the minimum wage will rise too.

- Run weekly auctions of minimum wage labor. The laborer submits an application containing resume, skills, and references to the Employment Auction Agency. Retail stores, restaurants, landscaping companies, etc, would then review the applicants and submit bids for workers. The bids could be $15 an hour, $8 an hour or $2 an hour. Perhaps there could be bids of negative $1 an hour, (there do exist workers with such anti-social habits that they have negative value to an employer). The employer offering the highest bid gets the laborer on a three month contract.

- Money coming out of progressive tax revenues then make up the difference. So if the employer bids $11, the government chips in $4 to make a total wage of $15 an hour.

- The worker gets a three-month contract. The employer can offer to renew twice. After that, the worker must go back into the auction. (The community does not want to be subsidizing the worker forever if some employer is willing to take on more of the burden). If the worker is fired without cause, they get paid some amount of severance. The employer can also dock pay for standard offenses, such as disobedience, tardiness, or surliness.

Voila! Everyone gets a job. The idle workers in burned-out inner cities and rust-belt towns are all now guaranteed gainful employment. Those working minimum wage jobs now get a decent income. At the same time, no additional costs are imposed on mom-and-pop restaurants struggling to make payroll. The subsidy comes from those with the ability to pay. There are some details and special cases to be figured out, but I think the general idea is sound.3

Now, I certainly do not like taxes. I do not want to raise taxes. Most Americans do not want taxes raised. That is why minimum wage increases are so seductive – they offer the promise of pay increases without costs to anyone. So if we are doing this redistribution via tax dollars, where does the money come from?

First, one could use this to generally replace most existing welfare programs, ranging from housing projects, to Section 8 vouchers, to food-stamps, to disability payments. Since everyone is guaranteed a job paying a living wage, there is no need for any further subsidy. Even people on disability can be given a job. Those with physical handicaps can be paid to watch security cameras. Those with schizophrenia are not crazy all the time. Surely there is some safe job they could find dignity in – whether that be cleaning up sidewalks or tending gardens in city parks.

Second, the subsidy money could come from reducing funding for schools. In the past fifty years there has been massive increases in the total amount spent on schooling, and the number of years of schooling. The theory is that since more schooled workers earn more, investing more in schooling will raise all wages. It is becoming more and more clear that this theory was totally wrong.

The reality is that schooling is a red-queen race – more years of schooling are needed simply to stay ahead of everyone else. Schooling is rarely value-add, and even more rarely is it value-add in a cost and time efficient manner. College graduates earn more because a degree signals to employers that the holder is conscientious and smart. But if everyone gets more degrees, it just devalues the signal, requiring everyone to get an additional degree to stay ahead. Thus as more and more people go to college, the marginal college students finds themselves graduating and working for customer support at Verizon or as a barista at Starbucks. Sending more people to school does not create more high-paying jobs; it does nothing to solve the imbalance between those with specialized, high-leverage jobs and those with commodity jobs; it does nothing to solve the problem of a global surplus of commodity labor. (To read more about the analysis in the paragraph, there are lots of more detailed links in the footnotes).4

By rolling back education to the level spent in the 1970s – a period in which America dominated the world in technology and innovation – hundreds of billions of dollars could be freed up to directly and immediately accomplish the end goal of creating a good job for every worker.

So that is my day-dream: a good job for every American, guaranteed, with no perverse impacts of the minimum wage, and no additional taxes. It could be accomplished next year, without any downside.

But it will never happen.

First, it is extremely hard to get public support for such a plan. Why? Well, who tells the public what to think? Schools. Academia. And journalists trained by schools and academia. Like any institution, these institutions always message how important they are. They teach that all economic advances are closely tied to schooling. They teach that to defund school is to defund our children. You would not want to shortchange our children would you? Are you against investing in our future? What kind of monster are you?

Second, the unfortunate truth is that policies are not enacted out of some sense of the general benefit. The truth is that programs are mostly supported by their bureaucracies. Let me prove the point in two pictures:

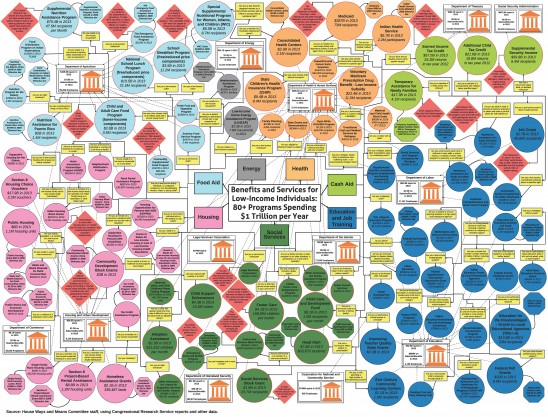

Picture one is a chart of all the welfare programs in the United States:

Such a system is not a product of intelligent design or human reasoning about what helps people. It evolved in slip-shod fashion, with each bureaucracy expanding its own turf, jealously guarding its own budget, and creating its own dependents.

The second picture is a graph of how total, after-welfare income changes with increases in employment wages in one state. You can see that for many people there is a trap. When you get a job making more money, you end up with less total income, because welfare cuts out:

Again, this is crazy. If one were trying to design a program to help people, no sane person would design it this way.

Another example: if you are a progressive American, you probably lament how the U.S. lacks the universal health insurance that Canada has. You wish that the anti-tax, anti-government conservatives weren’t so powerful here. Yet – here in the United States, per-capita government spending on healthcare is actually equal to the government spending in Canada. 5 And spending here is substantially more than in Britain. The U.S. government actually spends 65% more per capita than Singapore spends entirely, including both private and government. And Singapore has some of the best life expectancy and healthcare in the world. Once again, the U.S. is simply massively inefficient in the way it spends money on its welfare state. And yet, it is stuck this way. Why? Because if the U.S. were to implement a policy to make its healthcare spending as efficient as Singapore, that means that total spending would drop in half. That means half the people in healthcare would lose their jobs. Thus, should any such policy be proposed, everyone from the doctor’s associations to hospital executies to nursing unions to drug companies will band together to stop it.

One final example from a local news article (and this is not an isolated example, I have seen articles like this in other cities before): In Philadelphia, the housing authority is proposing a massive project to build 1,200 new units of affordable housing. Except Philadelphia has tons of housing – the city has lost population over the last three decades. The cost per unit of this new construction will be around $440k. Meanwhile in the private market houses can routinely be rehabbed and flipped at a profit for $150k. Cost of new construction is generally under $200k. Thus the housing authority is spending way more than it needs to, 60%+ of the spending is wasteful excess over what is actually needed to produce good housing. Why? Because the agency doesn’t actually care about optimizing its spending to help people. Like all bureaucracies, it has fallen prey to Pournelle’s law: “In any bureaucracy, the people devoted to the benefit of the bureaucracy itself always get in control and those dedicated to the goals the bureaucracy is supposed to accomplish have less and less influence, and sometimes are eliminated entirely.” (see my post on bureaucracy theory)

So imagine a plan was proposed: fund a universal jobs program via reducing funding for welfare and schools. What would happen? NPR and the New York Times would dispatch reporters to talk about it. They would interview policy experts (ie professors) and those working in the field (welfare case workers and administrators). Both would stand to lose enormously from my plan. Naturally, they would find all sorts of reasons for why the plan would be problematic and would cause all sorts of pain and strife. Popular support would be muddled and lukewarm at best, due to all this expert opposition. Few would risk their careers to push the plan through. The plan would die before ever coming to a vote.

So unfortunately, tragically, we are stuck. Our cities continue to suffer from low wages and high unemployment. The bureaucracy continues to expand and to solve none of these problems.

-

This scenario is obviously contrived. The most obvious objection is that in reality there are an unbounded number of possible jobs, an unbounded number of wants. The landlords do not just want food, they would hire those in the free labor pool to be servants, to make art, etcetera. And thus the competition over those laborers would drive up the wages. And I admit that this is very possible. But whether this is what actually happens depends empirically on the consumption desires of the landlords. What if, more than anything else in the world, the landlords desire days of going on fox hunts, and evenings feasting on fine steaks? Thus instead of paying out their surplus bushels of wheat to hire servants, they feed it to cattle. Furthermore, they convert some surplus farmland to hunting grounds. Now there are lots of unemployed starving farmers, and a few extremely low-paid working farmers, and fat landlords who eat cows and go on hunts. This possibility is not merely theoretical. Historically, we have examples of dukes and lords who prized having hunting grounds over all else. They could have cut down the forests and allowed more farmers to have farmland, and thus supported a larger caste of servants, but they did not. In modern times we see upper-class folk spending a lot of money on resource intensive activities such as world travel and eating paleo diets and avocados. One first-world person giving up meat could alleviate malnutrition among several Indians. But there is no job that the marginal worker in India can do for me, no service they can provide, that is more valuable to me than my diet of beef. Thus, my overall point is that the impact of a minimum wage on unemployment is an empirical question. Depending on the specific situation, the specific set of production opportunities, the specific negotiating positions, and the specific utility curves, you will get a different result.

↩ -

The IRS calculates total income at $9.1 trillion. The BLS calculated a labor force of 151 million employed full-time and part-time. Employment surveys state that the average employed American works 1799 hours a year.

↩ -

Here are some links supporting the argument that additional spending on schooling has done very little: the education myth, the magic of education, Tremble before the mighty sheepskin effect, Education Signaling: A fad whose time has come, Paul Campos on Career Opportunities, Master's are the new Bachelor's, What STEM shortage, Education and the Zero Sum Economy, College has been oversold

↩ -

In 2013, Canada spent an estimated $148.6 million Canadian for 35 million people, or $4,242. The US dollar and Canadian dollar started 2013 roughly at parity. In the U.S., total government spending was $4,197 per person.

↩